Monday, 19 May 2025

Why does your brain consume so much energy?

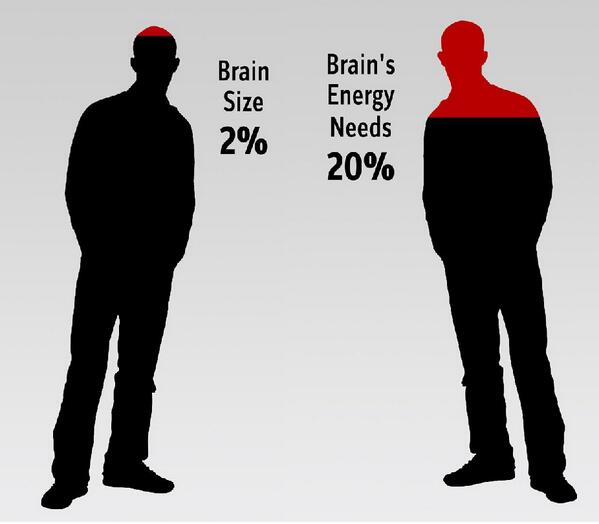

Your brain accounts for only about 2% of your body weight, but 20 to 25% of all the oxygen and glucose that your body consumes. Why this vast disparity? Until about 20 years ago, people tended to think of the brain as an organ that waited passively for stimuli and then reacted to them. But more recent neuroscientific research paints a very different picture of the brain, as an organ constantly engaged in intrinsic, spontaneous activity. Metaphorically, people used to imagine the brain as a calm, flat body of water, onto which a drop of rain occasionally fell and created a few ripples. Now scientists have shown us that the brain is a place where it is always raining, so that when one drop of rain falls, the small disturbance that it creates merges into something larger that is already highly active.

Your brain accounts for only about 2% of your body weight, but 20 to 25% of all the oxygen and glucose that your body consumes. Why this vast disparity? Until about 20 years ago, people tended to think of the brain as an organ that waited passively for stimuli and then reacted to them. But more recent neuroscientific research paints a very different picture of the brain, as an organ constantly engaged in intrinsic, spontaneous activity. Metaphorically, people used to imagine the brain as a calm, flat body of water, onto which a drop of rain occasionally fell and created a few ripples. Now scientists have shown us that the brain is a place where it is always raining, so that when one drop of rain falls, the small disturbance that it creates merges into something larger that is already highly active.

This major paradigm shift originated in the observation that the brain generates neural activity patterns spontaneously, regardless of what is happening in the individual’s environment. In your earliest stages of development, you may see no apparent connection between these patterns and the world around you. But they become more meaningful as you grow, acquire experience and begin to see how your actions in certain situations affect the world around you.

From the Simple to the Complex | Comments Closed

Wednesday, 23 April 2025

Our two ways of thinking and the inhibition of the frontal cortex

The human brain is often described as having two main ways of thinking: one of them fast, automatic and unconscious, the other slower, more flexible and requiring conscious control. Each of them has its own benefits and drawbacks. The first—let’s call it “System 1”—is based on the sum of the habits, stereotypes and received ideas that we have acquired since childhood. System 1 doesn’t provide us with any ready-made solutions, but instead sends us down paths to possible or likely ones. In contrast, System 2, with its logical, rational thinking, is slower and more careful. It proceeds by deduction, inference and comparison. System 2 is what lets us see past our conditioning and beyond appearances. (more…)

From Thought to Language | Comments Closed

Monday, 24 February 2025

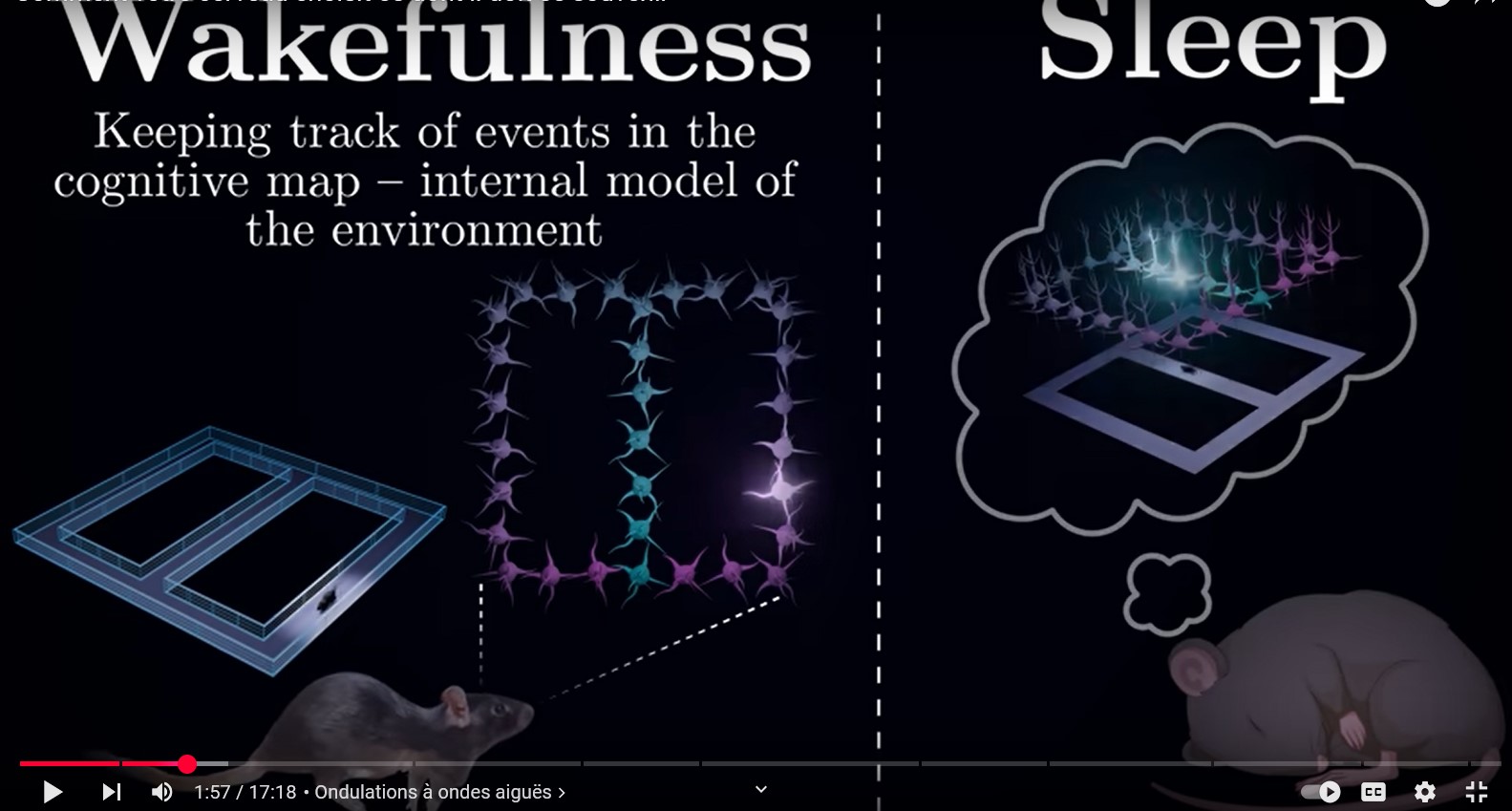

Truly amazing videos about the hippocampus

This week I want to encourage you to watch a video entitled “How Your Brain Chooses What To Remember”, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ceFFEmkxTLg. This video is one of many posted on the YouTube channel of computational neuroscientist Arsem Kirsanov. Kirsanov worked in the laboratory of neurologist Gyorgy Buzsaki , and Kirsanov’s videos about the hippocampus are truly amazing—in particular the one that I just mentioned. Not only does it present the content and methodology of a recent scientific article that is fascinating in itself, but it does so using a brilliant instructional approach with outstanding visuals. (more…)

Memory and the Brain | Comments Closed

Friday, 31 January 2025

Humans: The species built on interdependence among its members

For we humans, the most important part of the ecosystem that we live in is definitely the other human beings who live in it. We have thus developed a strong interdependence by discovering, at a very early age, our need to cooperate with one another and the benefits that this cooperation brings. If you need any proof how much human children are naturally inclined to help one another, all you need do is watch the videos shot by psychologist Michael Tomasello . (more…)

Emotions and the Brain, From Thought to Language | Comments Closed

Monday, 23 December 2024

Us versus them: between hope and hopelessness

Phenomena such as racism, sexism and ageism become more understandable in light of our strong biological tendency to divide the world into two groups: the one we belong to, and everyone else. In all primates, including humans, the sight of a stranger causes the brain to activate its “danger” pattern in less than a tenth of a second, especially if that stranger’s skin is a different colour from our own. As humans, we can use language to rationalize why any given group is inferior to our own, and we can attack its members in a wide variety of ways, ranging from verbal microaggression to genocide. The opposite is also true. As many studies on intra-group favoritism have shown, if you get into trouble while attending a sporting event and you’re wearing one of the competing team’s jerseys, that team’s fans are the ones most likely to help you. (more…)

From Thought to Language | Comments Closed