Wednesday, 28 August 2019

Shifting Paradigms in the History of Neuroscience

The development of a scientific discipline over time is often far from a linear sequence of events that build on each other logically. That can happen, of course. But philosophers of science, such as Thomas Kuhn, have clearly shown that “normal science” often operates under a dominant paradigm for an extended period, until enough “abnormal data” (i.e., data that contradict that paradigm) accumulate to lead to a scientific revolution, accompanied by a radical shift in that paradigm.

The development of a scientific discipline over time is often far from a linear sequence of events that build on each other logically. That can happen, of course. But philosophers of science, such as Thomas Kuhn, have clearly shown that “normal science” often operates under a dominant paradigm for an extended period, until enough “abnormal data” (i.e., data that contradict that paradigm) accumulate to lead to a scientific revolution, accompanied by a radical shift in that paradigm.

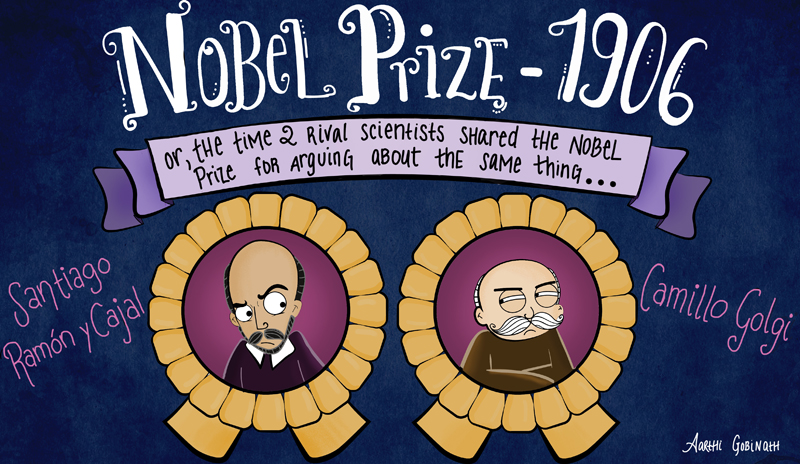

One of these revolutions, famous in history and entertainingly presented in the Neurohistory Cartoons Project, broke out when the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine was awarded jointly to Italian scientist Camillo Golgi and Spanish scientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal. In Golgi’s speech accepting the prize, he defended the then widely accepted “reticular theory,” that the nervous system formed a physically continuous network in which the cell bodies were simply more important nodes. Immediately afterward (and, ironically enough, on the basis of microscope observations using a stain developed by Golgi), Cajal defended his new “neuron theory,” that the nervous system was composed of neurons, each of which was a distinct, separate cell. I don’t know what the atmosphere in the room was like after these two conflicting speeches, but the fact is that Cajal’s theory was gradually adopted by the scientific community as further data emerged to support it (for instance, the subsequent discovery of the chemical synapse and the neurotransmitters by which it operates).

But over the past few decades, neuroscientists have observed that synapses of another type — electrical synapses, formerly associated more with invertebrates — are actually far more common in the neurons of the human cortex than was once believed. And the more that scientists study electrical synapses, the more that they turn out to be complex and to serve a variety of functions, such as when axo-axonal electrical synapses synchronize the activity of neighbouring pyramidal neurons. In other words, the data are now revealing something very much like the continuous network originally posited by Golgi! As so often happens in biology, the truth turns out to be a matter not of one or the other, but rather of one and the other!

From the Simple to the Complex | Comments Closed