Wednesday, 8 January 2020

The Glymphatic System: The Sewers of the Brain

As has been well established, the human brain consumes tremendous amounts of energy: about 20 to 25% of all the energy that the body uses, even though this organ accounts for only 2% of the body’’s total weight. As a result, the brain necessarily produces large amounts of waste—the equivalent of its own weight in waste every year! But this waste can be toxic to the brain itself. How the brain gets rid of this waste was long a mystery to scientists. Some thought that the brain might cleanse itself through passive diffusion of cerebrospinal fluid from the cerebral ventricles, but this seemed like a very slow waste-removal mechanism for such an active organ as the brain. It was not until 2012 that studies on mice showed that the brain has its own specific waste-removal mechanism that is faster and more efficient..

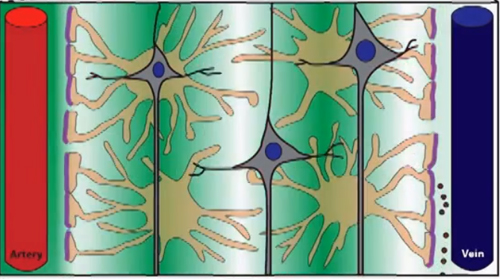

Every artery, vein and capillary in the brain is surrounded by a perivascular space defined by the extensions of the astrocytes (a type of glial cell) that completely surround these blood vessels. The cerebrospinal fluid that bathes the brain enters through the perivascular spaces surrounding its arteries and exits through the perivascular spaces surrounding its veins (see image above).

This system is called the glymphatic system, to indicate that glial cells play the same role here that the lymphatic system does in the rest of the body: draining waste from its various tissues. The reason that the glymphatic system was discovered only recently is that it cannot be seen in brains examined post mortem. It was only with the development of a method known as two-photon microscopy that scientists could view the flows of blood and cerebrospinal fluid in the brains of living animals in real time.

This recent discovery meshes perfectly with another one, discussed in a previous post in this blog: the presence of lymphatic vessels in the dura mater, one of the three meninges (membranes) surrounding the brain. This discovery also sheds light on other scientific observations, such as the fact that during sleep, the intracellular space in the brain increases by up to 60%, most likely to allow better circulation of the cerebrospinal fluid. For example, β-amyloïd protein (whose accumulation seems to be connected with Alzheimer’s disease) appears to be removed from the brain two times more efficiently when mice are asleep than when they are awake.

And that is only one example of the protective roles that sleep plays. In recent years, scientists have developed impressive data on how sleep helps to protect the organism from a great many different pathologies.

From the Simple to the Complex | Comments Closed