Tuesday, 13 October 2020

Our perceptions are shaped by the possibility of imminent actions

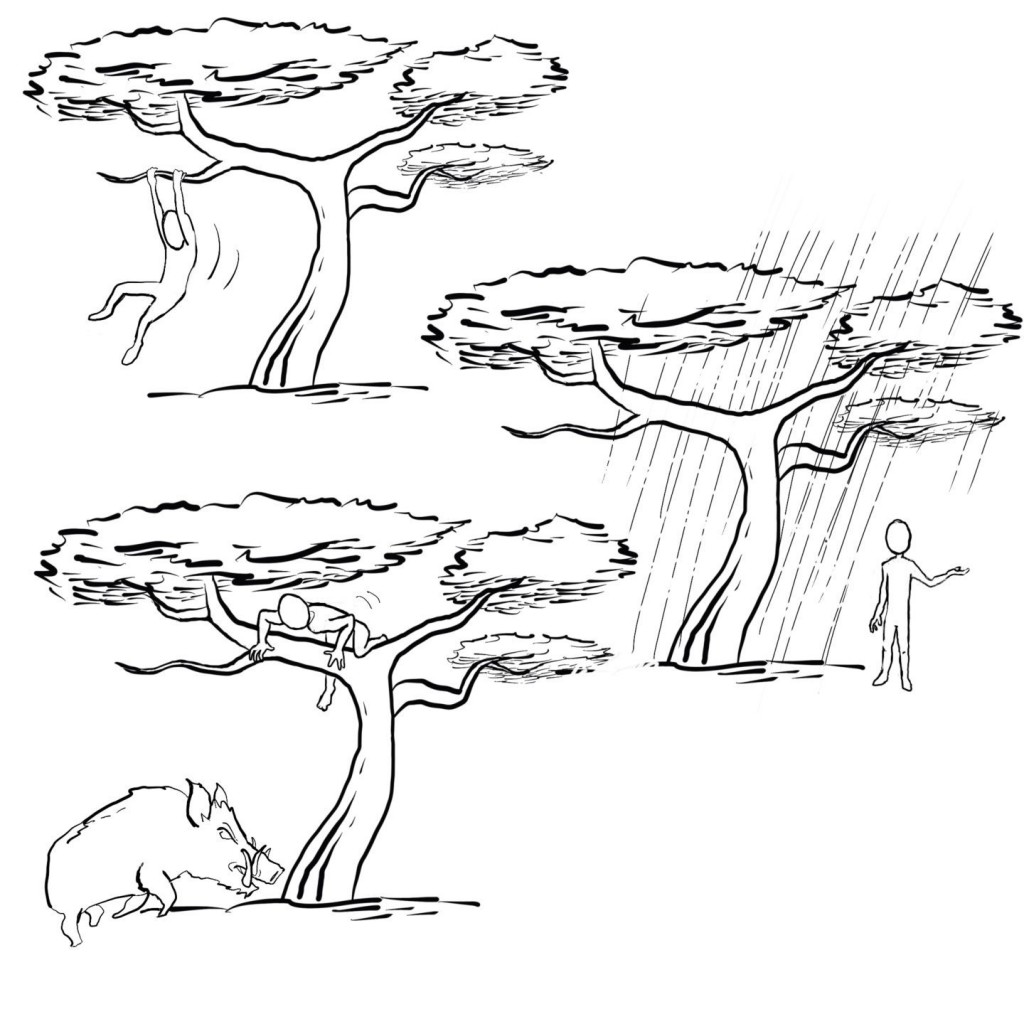

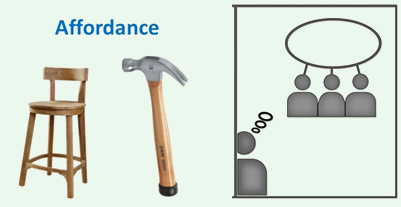

Affordances are a key concept in cognitive science, first advanced by J.J. Gibson in 1966. As I explained in an earlier post in this blog, an affordance is an opportunity that an object offers to take action. A hammer, for example, offers the opportunity to be grasped by its handle, and a chair offers the opportunity to sit down. What is interesting about this concept of affordances is that the opportunity for action does not depend on an object’s characteristics in any absolute sense, but instead is relative: it depends on the possible relationships that a particular organism may establish with that object. A tree, for example, offers different affordances to humans, who may use it as shelter from the rain, or crows, which may use it as a perch, or to woodpeckers, which may use it as a place to hunt for food. Moreover, as the above illustration suggests, any given object (again, such as a tree), may inspire different affordances for a given organism (such as a human) depending on that organism’s motivations and/or the broader general situation. (more…)

Body Movement and the Brain | Comments Closed

Thursday, 1 November 2018

How the Concept of Affordances Has Evolved

Recently, I had the chance to realize how quickly a concept can change—in this case, the concept of affordances, In its original form, this concept first appeared in studies by James J. Gibson on the sense of sight, in the 1970s. In short, Gibson observed that when we see an object, what interests us the most is not so much its physical properties as the opportunities that it affords us to take action—to intervene more effectively in the world and thus better resist the ravages of time, or, in the elegant language of physics, to temporarily overcome the second law of thermodynamics, that entropy always increases.

For some years, this concept of affordances received little attention in cognitive science, because the prevailing highly computationalist paradigm, emphasizing inputs, manipulation of symbols, and outputs, militated against its full development. This is a common phenomenon in the history of ideas: a conceptual innovation that is just a bit ahead of its time does not fit into any existing, broader paradigm that would let the scientific community understand and embrace its full implications. (more…)

Body Movement and the Brain | No comments

Thursday, 26 October 2017

The Brain, The Body and the Environment: We Need All Three To Make Thinking Possible

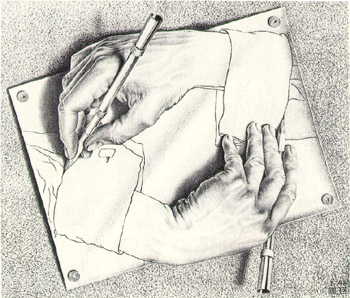

The third and final session of my course at UPop Montréal started by asking whether our brains really process our most abstract concepts in the way proposed by cognitivist theory: that is, as arbitrary symbols that have nothing to do with the sensory modalities by which these “inputs” are entered. But as early as the 1960s, experiments with the mental rotation of objects seemed to suggest that, on the contrary, when we perform “high-level” mental manipulations of this kind, we employ the sensory regions of our brain to do so. (more…)

Body Movement and the Brain | No comments