Thursday, 11 February 2021

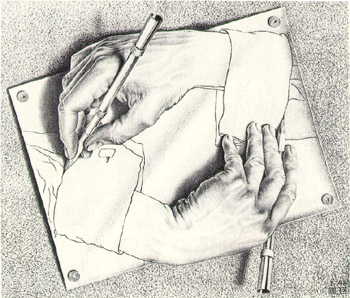

Revisiting an optical illusion in terms of predictive processing

I recently came across a little experiment that I posted years ago on this website to show how the blind spot in each of your eyes works. The blind spot is a part of the retina where there are no photoreceptors, because it is where the axons of the retina’s ganglion cells converge and exit the eye, forming the optical nerve. As a result, there’s a corresponding area in your field of vision that doesn’t register on the retina. Hence, in theory, you shouldn’t see anything there. But in reality, you don’t see any such blank spot in your field of vision.

I recently came across a little experiment that I posted years ago on this website to show how the blind spot in each of your eyes works. The blind spot is a part of the retina where there are no photoreceptors, because it is where the axons of the retina’s ganglion cells converge and exit the eye, forming the optical nerve. As a result, there’s a corresponding area in your field of vision that doesn’t register on the retina. Hence, in theory, you shouldn’t see anything there. But in reality, you don’t see any such blank spot in your field of vision.

To find out why not, let’s revisit this optical illusion from the standpoint of predictive-processing theory, which has become more and more accepted in cognitive science over the past 10 years or so. (more…)

The Senses | Comments Closed

Friday, 4 October 2019

Karl Friston: toward a grand unifying theory of life and cognition?

This week I’d like to tell you about a fascinating piece of reporting by journalist Shaun Raviv, in the November 13, 2018 issue of Wired magazine. It’s about one of the most important figures in the cognitive sciences today: Karl Friston. I call Raviv’s piece reporting rather than an interview because he spent more than a week in London in the summer of 2018 researching it. Its title, “The Genius Neuroscientist Who Might Hold the Key to True AI”, might seem sensationalistic, since we all know what a buzzword artificial intelligence has become. But in fact, this title understates the case. As Raviv puts it, “Friston believes he has identified nothing less than the organizing principle of all life, and all intelligence as well.”

This week I’d like to tell you about a fascinating piece of reporting by journalist Shaun Raviv, in the November 13, 2018 issue of Wired magazine. It’s about one of the most important figures in the cognitive sciences today: Karl Friston. I call Raviv’s piece reporting rather than an interview because he spent more than a week in London in the summer of 2018 researching it. Its title, “The Genius Neuroscientist Who Might Hold the Key to True AI”, might seem sensationalistic, since we all know what a buzzword artificial intelligence has become. But in fact, this title understates the case. As Raviv puts it, “Friston believes he has identified nothing less than the organizing principle of all life, and all intelligence as well.”

What Friston offers is the kind of (very) grand unifying theory that doesn’t come along in science every day. But who is this guy with such big ideas? (more…)

From the Simple to the Complex | No comments

Tuesday, 9 January 2018

The Baseball Batter’s Predictive Brain

For some years now, cognitive scientists have increasingly come to regard the human brain as a machine for making predictions. In other words, these scientists think that our brains spend most of their time trying to figure out what is going to happen next so that they can take action accordingly. The great adaptive value of such a process is immediately obvious.

The theoretical framework underlying this view of things is extensive and fairly new, although it has roots in 18th-century philosophy. Some authors even describe it as a paradigm shift, the same term that has been applied in turn to the cognitivist, connectionist and embodied dynamic approaches over the past half-century. (more…)

Body Movement and the Brain | No comments

Thursday, 26 October 2017

The Brain, The Body and the Environment: We Need All Three To Make Thinking Possible

The third and final session of my course at UPop Montréal started by asking whether our brains really process our most abstract concepts in the way proposed by cognitivist theory: that is, as arbitrary symbols that have nothing to do with the sensory modalities by which these “inputs” are entered. But as early as the 1960s, experiments with the mental rotation of objects seemed to suggest that, on the contrary, when we perform “high-level” mental manipulations of this kind, we employ the sensory regions of our brain to do so. (more…)

Body Movement and the Brain | No comments